Section I Extra Credit Posts for Spring 2023

Since I moved the exam back by 1 week, only posts below here (January 30th or earlier) will potentially be sources of extra credit questions on Exam 1.

For January 30th

We get U.S. macroeconomic data from more than one source. Some comes from the BEA. Another big source is the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS.gov). We also get some from the Census Bureau (they don't just sit around for 10 years between each decennial population census).

These agencies release many different measures of the inflation rate (used for different purposes). An important one, because it's used by policymakers in D.C., is the PCE. Measures of this are released at the same time as GDP. Last week's announcement showed a rate of 3.2%/year during 2022 IV. You can find this on FRED, although it might not be the top link in Google. Today it was the second one, and the codename for the data series is PCEPI. If you go there, it shows a graph in which the last couple of years of higher inflation are the steep part on the right.

For January 27th

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is how we measure the size of macroeconomies. The latest estimate of U.S. GDP came out Thursday.

These releases are scheduled in advance, but generally at 6:30 Mountain time on the 4th Thursday of the month.

GDP is collected by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA.gov). Here's the news release.

GDP is measured as a flow, so it's never available until after the time period ends (so the flow is finished), and then after a delay (to collect data).

The U.S. measures their GDP on a quarterly and an annual basis.

In the U.S., this is done like how you're supposed to write an English paper: draft, revision, and final version. What we got last week was the draft (called the Advance Estimate). The others will come out in 1 month and 2 months.

It showed a real GDP growth rate of 2.9%/year, annualized. Compare this to the figure in Chapter 6. That rate was a few tenths of percentage point better than expected.

GDP for the U.S. is now $26.13 T/year, or $26,130,000,000,000/year.

***

I also showed you in class that the keyword FRED can be helpful for finding macroeconomic data (like GDP). FRED is a database of free and publicly available data, mostly for the U.S. It is maintained by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, which we'll talk about a bit in Chapter 11.

Same deal as Monday. Go look at "Some History of Congressional Budgeting" in SUU Macroblog. For this one, the post is short, but the articles in the two links are required.

For January 23

An easy one for that.

Sometimes I write something up for the blog for the ECON 3020 class, and then use it for this class. For you folks, that's always the single post I link to (for 3020, they're responsible for all posts on the blog).

So for today, go take a look at "Yes I'm Being Conceited (and Proud)".

For January 20

Once again, the debt ceiling is in the news. Go ahead, google "debt ceiling news". I got almost 2 million hits. The Wall Street Journal generally has the best coverage of macroeconomic issues, so here's one of their pieces on this entitled "U.S. Nears Debt Ceiling, Begins Extraordinary Measures to Avoid Default."

It's going to be this way your whole life. It is an issue that only goes away temporarily. So much so that you could estimate each time how much breathing room they've given themselves until it comes up again.

My guess for this time is that they stretch it out all spring, and then do a quick fix that pushes it off until early 2025.

What is going on this week is the the (U.S. Department of the) Treasury is going to start using some "extraordinary measures" to avoid hitting the ceiling this week, but those will only last about 4-5 months. This doesn't mean much more than the standard things you do when you're short of cash: figure out which bills have to be paid first, pay them, and start stalling a little on the others.

First off, do not panic or overrate this, or listen to people who do. The government isn't broke, and it can pay its bills.

Secondly, panic a little. In representative democracies, parties with slim majorities tend to get dominated by their stupidest/craziest members. It happened to the Democrats over the last 2 years (with a 216-213 majority 2 troublemakers can control things), and it's going to happen with Republicans over the next two (with a 222-212 majority, 5 troublemakers can control things). It's a common enough situation that both managerial economics and political science teach about "hostage negotiation" (which in this context means a vote or decision is being held hostage, not a person). So yeah, it's possible they may try and screw things up.

Third, part of that is going to be finding our sensitive spots, and manipulating them until one side gives in. For example, a few years ago, they "addressed" the lack of an agreement on the debt ceiling by closing all the national parks down until an agreement was reached. It worked. It always does. If it sounds like an unstable person engaging in self harm to get attention ... you're starting to get how this works.

The situation is that our government is set up with checks and balances. The legislative branch (Congress) decides on the amount of spending and taxes. But the executive branch (the Treasury) actually does bill paying. Just like you, if outflows of money exceed inflows, the difference must be borrowed. But the legislative branch sets the limit (a ceiling) on how much the executive can borrow, including all the past borrowing that hasn't been paid down (the national debt). What has happened this week is the Treasury has told Congress they need to raise the debt ceiling, or they'll have to cut spending or raise taxes. Legislators don't like to do any of those three.

Let's draw an analogy. Imagine an actor who's pretty good at doing things to make money flow in, but even worse at buying stupid stuff. (Ooh ooh, we don't have to imagine, it's a thing: we can just use Nicolas Cage as an example). Now suppose he has a manager that pays all his credit card bills by

check. Every once in a while the manager calls Cage and tells him if I send the check this time it will bounce. But maybe in the short-run I can pay the bill on one card with the other, and get away with that for a few months. And Cage's response in the longer-run is to find a card with a higher credit limit at the last minute.

More formally, this is how Jason Furman, an economist from the Obama administration explained it on NPR on Wednesday:

Congress has to give Treasury permission every time it goes out and borrows money, which it has to do quite a lot because we spend more than we collect in taxes. Starting about 100 years ago, they gave a blanket permission that you can borrow up to a certain amount, and you can't borrow past that even if you're borrowing money to pay bills that Congress itself passed a law saying you have to pay.

If it sounds ridiculous, it sort'of is.

Back in the 1970's, Congress passed a law governing how it works that separated the spending amount from the tax revenue amount. And spending is usually bigger because raising spending gets you votes and raising taxes does not. So they don't have to match up, and they usually don't. Borrowing makes up the difference.

But, here's another one of those bits of "folk macro" that most of you have. And most people have this completely backwards. The reality is that the U.S. government is the best and most reliable borrower the world has ever known. In short, everyone wants to loan it money. All. The. Time. The "folk macro" is that people think there's a limit on this. There isn't. All I can tell you is that the limit is so huge no one is even sure it exists. So much so that claiming there's a limit is a good sign the speaker really doesn't know what they're talking about. But like all folktales, try telling a true believer that Mike and Sulley are not in their closet, or Randy isn't under their bed.

I do think we're going to see a nasty political fight over the next 4 months. The Republicans, as a party, are convinced the government is too big. And stalling on the debt limit is one way to force others to vote for some spending reduction.

And, we've had a big spending blowout over the last 3 years, so there's certainly an argument to be made that they can back off some things.

In fact, you can probably view it as incompetence on the part of Democratic Congressional leadership that they didn't get the debt ceiling increased before the elections.

Lastly, another piece of "folk macroeconomics" that people get wrong is the idea that the Republicans hate spending and will cut it by much. I will admit that the Republicans prefer spending less than the Democrats. But not by much. The sentiments of the two parties are a lot closer to each other than they are to you and me. And the job of member's of Congress is to spend other peoples' money: who'd want to do less of that?

For January 18

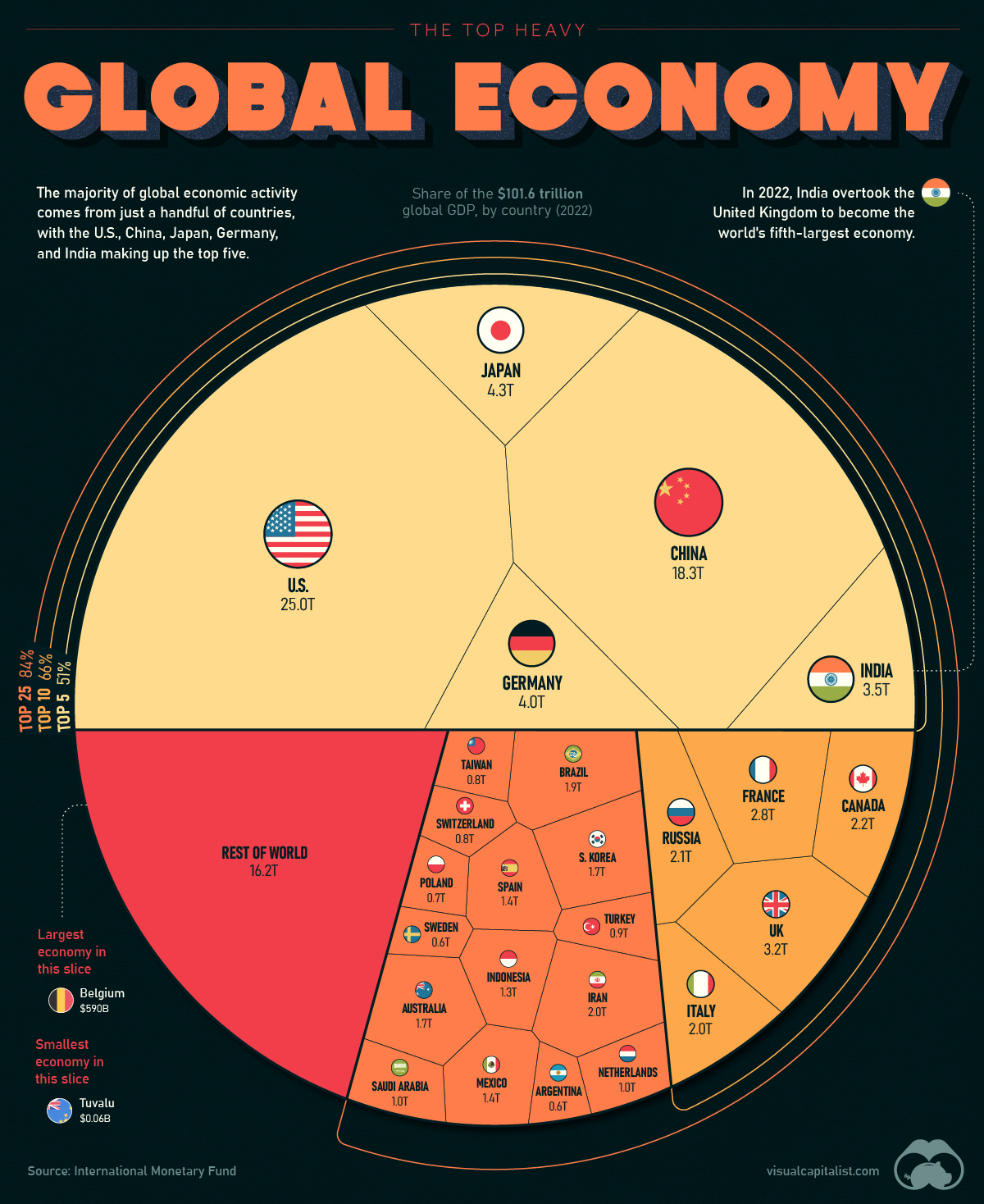

Just a simple infographic from Visual Capitalist for today, showing the relative size of macroeconomies around the globe:

The major determining factor here is actually population. Richness explains some of it, but not as much. So the big ones at the top are all places where a lot of people live. For example, people in the U.S. are richer, but there are a lot more people in China, so we're about the same size. India has about the same number of people as China, but they're much poorer on average, making their economy smaller.

Also for January 13 (This post will not be used for extra credit questions)

I mentioned cuneiform tablets in class.

There's been a meme that's kind of big the last few years that references one of these, known as the "Complaint Tablet of Ea-nasir" It looks like this:

Like most memes, who knows why the heck this got popular. But it did.

Most of the memes are a variation on this rough translation.

Ea-nasir traveled to trade for copper. He brought it back to trade with Nanni. Nanni sent a servant with something to exchange for the copper. When he got there, it was low quality so he refused it. Ea-nasir wrote Nanni asking why his servant had done that, and Nanni wrote back and sent the tablet shown above, detailing the quality complaint and noting that to boot Ea-nasir had been rude to the servant. This all happened roughly 3,800 years ago.

For January 13

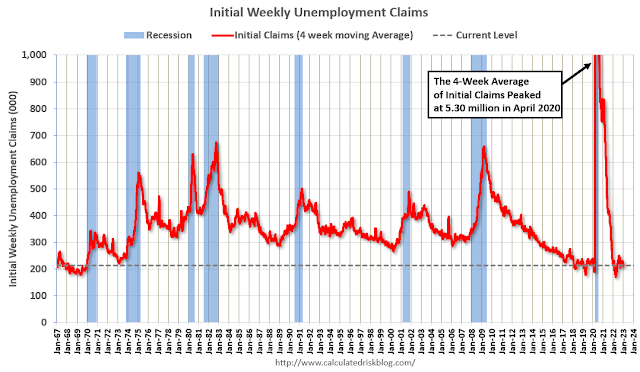

We looked at a post entitled "Weekly Initial Unemployment Claims Decrease to 205,000" on the blog Calculated Risk.†

To get unemployment insurance checks, you have to go to a government office and claim that entitlement. After every week, the Bureau of Labor Statistics releases a count of how many people did that.

This is not the number of unemployed. It is the number of newly unemployed. The number of unemployed would be the accumulation of those new claims, subtracting out the people who got jobs or stopped looking.

That number, 205,000, is big and seems kind of scary at first glance. But recall that it's a big country. Out of a population of 330,000,000 it's not that big (less than a tenth of a percent).

Even so, the number of initial claims matches up pretty well with recessions:

Now, all macroeconomic data is a gray mess of mixed signals. It's great that new claims are so low compared to where they've been in the past. But part of the reason for that is that new hires are so hard to come by that bosses don't want to fire the jerks and other poor workers. That's not so great for the rest of us.

† Calculated Risk is not a very entertaining blog. But you'll see it a lot in here because it's nothing but macroeconomic data, reported neutrally, and it's free.

For January 11

Why do we study macroeconomics?

This is a pretty fundamental question, that honestly, a lot of professors and texts are not very good at answering.

But I've got a pretty good answer. We study macroeconomics because our (economic) lives are affected by these things that are bigger than us.

One big one is positive geographic correlation. That's best illustrated by a satellite view of the Earth at night:

We tell each other we live in America, or Utah, or wherever ... but the truth is almost everyone on the planet lives where you see lights.Correlation means things go together. Positive correlation means things move together in the same direction. Positive geographic correlation means we choose to live near other people, and to build new communities ... right next to old ones.

But no one chose or planned the particular pattern shown in that image. It happened whether we wanted it to or not, but we all have to live with this reality. There are situations like this all over the natural world: for example, we call them sandpiles because bunches of sand are never cubes or spheres or whatever. With sand, we take that for granted. With economics, we'd like to move beyond that and study why we get the patterns seen in those lights.

We also get something called positive temporal correlation. This is the idea that life — for most people — is better this year than last, and will be even better next year. If you were to graph that out it would look like an upward slope.

Again, we didn't choose that. For most of human history ... the years were pretty much the same ... and there wasn't systematic pervasive improvement in well-being. But now there is. Why is that? We study macroeconomics to try an get an answer to that.

You can take advantage of positive geographic correlation by moving to places where your life is likely to be better.

You can't do much to take advantage of positive temporal correlation (until we can hibernate like in science fiction movies). But what we do know is that for most of us, the quality of our life will be better at 60 than it is at 40 or 20. You're probably better off than your grandparents were at your age. You'll probably also be better off in the future when you reach the age they're at now.

Comments

Post a Comment