Section 3 Extra Credit Sources for Fall 2022

For November 15:

Personally, it's hard to write these posts sometimes. I want to do a little every day, but some days, or weeks, not much happens macroeconomically. :( That's the way Fall 2022 was. Election years are like that: no one wants to rock the boat right before an election. Voters might remember something recent. But over the last couple of weeks, the macroeconomic news has been blossoming like crazy. :-o

I have tried to limit my linking. Most of this can be found just by googling.

A good way to keep on top of this story is to go to the complementary online Wall Street Journal subscription you have, and look for the link that says "Today's Action" at the top of the page. Sorry, I can't direct link to that (it changes all the time).

***

There is a full-blown "bank" run happening right now, except it's not in the banking industry, it's in the cryptocurrency exchange industry. Both are part of the financial sector (and I'm using sector and industry interchangeably here).

Bank runs are rare. They were not that rare a century ago.

It seems that deposit insurance works. But macroeconomic policy is non-experimental: we can't control or do away with all the other stuff that might influence financial markets. Maybe deposit insurance is useless, and we're just fooling ourselves. It doesn't seem so, but don't forget that possibility.

Banking is one of the most heavily regulated industries out there. Get the causality right: it is regulated because bank runs did happen; it is not bank runs happen so we need more regulations.

But complying with regulations is costly. Those costs are paid out of the the interest earned from lending, reducing the amount that can get paid out to depositors. So depositors look for places to put their money that are bank-like, but less regulated.

These are called shadow-banks. The financial crisis in 2006-9 had runs on shadow-banks.

Cryptocurrency is stuff like bitcoin, ethereum, and a host of others. People who haven't had enough macroeconomics think cryptocurrency is special because it's created inside the financial system but without banks. Those who have had macro through Chapter 10 should respond with — "Duh. Tufte and the Colander text taught me about inside money".

A lot of cryptocurrency is handled through exchanges. If it's money, there has to be someone you can exchange it with or it doesn't have value. So these exchanges host accounts for cryptocurrency, and allow you to exchange it with others, sometimes for stuff that isn't cryptocurrency. People who haven't had enough macroeconomics think cryptocurrency exchanges are special because they provide intermediation. Those who have had macro through Chapter 11 should respond with — "Duh. Tufte and the Colander text taught me that the financial system is us and intermediation is how we're connected together".

So anyway, cryptocurrency exchanges are shadow-banks. You can earn more in them because they're not as regulated as banks. For that, you get a greater risk of runs.Bingo.

The run started with breaking news about a particular cryptocurrency exchange called FTX about 10 days ago. Basically, the money wasn't where it was supposed to be. It doesn't matter if it's currency or cryptocurrency: if the money is there you trust, and if it's not you don't. Now it's leaked out slowly over the last week that FTX's management was doing sneaky stuff (here, and here). But nothing we haven't seen in other institutions: it doesn't matter if it's fraud or cryptofraud — if your money was used decently you trust, and if it's not you don't. Oh, and the principals in FTX were making (ridiculously) huge campaign donations to one party. Those who have had macro through Chapter 12 should respond with — "Duh. Tufte and the Colander text taught me that rent seeking is a common problem when we fool ourselves into thinking the regulators aren't human.

The phrase tossed around for this in finance is "the math always wins". Basically, if you do the math right, and the answer you get it contrary to the reality you see around you, eventually reality will change. In short, if you think everything is different this time, think again.

***

No macro in this section. But don't you think people should have been suspicious when it became public that the principals of FTX were cohabiting in a $40M penthouse in an exclusive gated community in The Bahamas, replete with MIT graduates, children of Stanford and MIT professors, Harry Potter fanatic larping aficionados, and a secretive Asian-American computer coder who doesn't seem to have ever talked to actual humans very much? It sounds like James Bond villains for the age of wokeness.

***

On the subject of the demands for regulating cryptocurrency exchanges that are going to crop up very soon, here's Scott Sumner writing at Econlog (retired macro professor who worked at Bentley College):

So what’s the argument for new regulations of crypto? Surely not the fact that Bitcoin prices have plunged by 75%? Surely not the fact that creditors to FTX are going to lose their money? Surely not that fact that there are accusations of fraud in the recent FTX collapse? These are all either normal parts of our financial system, or are already outlawed by regulation. So what is the specific argument for additional regulation of crypto? To “protect crypto investors”? Why would we want to do that? To protect the banking system? I’ve seen no evidence that crypto threatens the banking system.

Do we really want to make people who invest in crypto feel safer about their investments? Wouldn’t that make “bubbles” even more likely? Isn’t it healthy for crypto investors to fear they might lose their investment? Wouldn’t it make them more careful?

...

Again, there may be market failure arguments of which I am unaware. But “bankruptcy and fraud” are not textbook examples of market failure that require regulation. One is a part of any well functioning market, while the other is already illegal. It may seem obvious to you that “something must be done”, but it is not at all obvious to me.

***

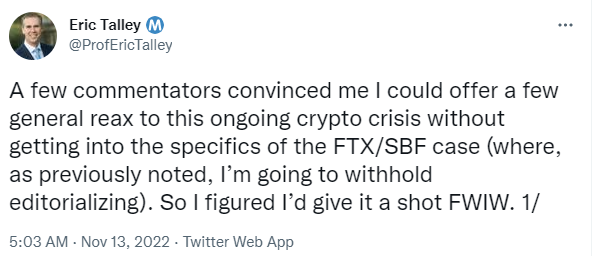

And here's a tweet storm from Eric Talley (a professor of financial law at Columbia). Reproduced in full since tweets can be hard to link to permanently:

We talk a lot in contemporary society about the importance of "lived experiences". Talley's lived experience and mine are just about the same. Perhaps the world would work better if we paid more attention to the lived experiences of people with some expertise in something worthwhile.

***

Still curious? Last semester, student RC recommended (and I finally watched) the documentary "Line Goes Up" on YouTube.

For November 10:

Let's go easy today. The BLS will announce the inflation rate of the CPI at 8:30 am EDT. I was able to update this morning, highlighted below.

Calculated Risk has the expectations:

The consensus is for a

0.7% increase in CPI, and a (0.4%/year actual)

0.5%/year increase in core CPI. The consensus is for CPI to be up (0.3%/year actual)

8.0%/year year-over-year and core CPI to be up (7.7%/year actual)

6.6%/year YoY. (6.3%/year actual)

(I'm not sure where he gets the "consensus" from, but he's the type of person who would collect that data on the side, just for fun. In turn, that different investment advisors, like Goldman Sachs, produce their own expectations for sale to clients).

Most of any "news" tomorrow will be whether the actual numbers are a surprise compared to those. Remember to think clearly about this: the actual numbers are not good, they're awful. But even awful numbers can be better than expected. Also, this is measuring something that already happened, so we lived through the awfulness, thus the response to finding out it was not-quite-so-awful will be positive.

EVERYTHING ABOVE HERE WILL BE COVERED ON EXAM 4.

For November 8:

This is also a two-fer.

For macroeconomics professors who have to write up extra credit topics, macro-ignorance is the gift that just keeps giving ;-D

A poll shows that 63% of Americans want more stimulus checks from the government to help address their difficulties with inflation.

Except this is the most likely source of the inflation we already have, so more checks will make it worse.

Fundamentally, inflation is about having more spending than production. Sending out more checks would increase spending without encouraging anyone to produce more. Therefore, more inflation.

Having said all that, should an individual be against getting a stimulus check if it helps them? No.

What we have here is a fallacy of composition: something that is good (or bad) at the micro level that is bad (or good) at the macro level. This is covered in Chapter 8.

It's also an example of a different thing, not covered in this class, called a prisoners' dilemma. In this, opposing parties each make the right choice for themselves, but the combination of those right choices produces the wrong outcome. In this case, everyone wants help from the government, but providing that makes things worse.

What we should work for (and hope for) is that policymakers understand this, and don't give in to the demands of individual voters. The track record on this is not good.

***

There's a video for this one, excerpted from the Q&A during Fed Chair Powell's press conference last Wednesday (you can go and read the transcript if you prefer, I'm interested in the question by Nick Timiraos and the response.

Timiraos question and Powell's response are full of jargon — but it's the terminology you're learning right now. Listen carefully.

Inflation is not fun. Perhaps the worst thing about it is that it's costly to fend off, and most policymakers do not have the guts to do so.

A sign of this is denial. It is not bad advice going forward for you to worry most about inflation when policymakers are downplaying it, as the Biden administration has done for the last 18 months. They often are supported by credulous journalists, and the fraction of people in the financial sector with positions that will lose money if interest rates go higher.

Timiraos (long-winded) question is asking if (nominal) interest rates will have to go above the inflation rate (and he describes a specific measure) for policy to be contractionary enough to bring the inflation rate down.

Powell's response hits on the Chapter 11 topics of the Taylor rule, forward looking measures (he means expectations of the inflation rate rather than the inflation rate itself), multiple components of nominal interest rates, the real interest rate, spreads (the yield curve), and whether policy is already contractionary ... in under a minute.

And he's saying interest rates are going to need to go up at least a couple, and maybe several points, before we start to see inflation coming back down.

I'm not bragging here: solid macroeconomics professors have been teaching their students this for 4-5 semesters already. This isn't hard. It's obvious. What is hard for students is that pundits and politicians will say just about anything to avoid this hard reality.

For November 3

I've got a triple today, since something new came up.

People out in the general public like to assume that the government knows what it is doing macroeconomically. This is mostly because ... well ... governments tell us a lot that they know what they're doing macroeconomically. Not so.

This is a slam on the Biden White House, mostly because it happened yesterday. Stuff like this happens to both parties. The reason for this is that macroeconomics is a lot of what they do, but the jobs are mostly filled by politicians and bureaucrats (rather than economists). (Personally, I'm not claiming economists would do a better job, just that you should recognize that it's not exactly government by experts, right?).

So here's what happened. I think you've learned enough macroeconomics to see what the problem is. Someone sent this out as an official White House tweet.

Seniors are getting the biggest increase in their Social Security checks in 10 years through President Biden's leadership.

— The White House (@WhiteHouse) November 1, 2022

Is this true? Yes.

Is it a good thing? Why is that?

Within a short time, this bit of government stupidity blew up on Twitter, and this tweet was deleted before everyone could see it.

Why does stuff like this happen? Most likely it's due to non-economists having latitude to make claims about economic issues without adequate supervision.

***

So, the FOMC was expected to raise their interest rate target by 0.75% (75 basis points), and they did.

Here's the home page of the Fed, and as I write the statement from the FOMC is at the top of the page. (Note that the statement doesn't actually say 0.75%. Instead it says the new target range is 3.75% to 4.00%, while before it was 3.00% to 3.25%. The people who read these statements for their job already know that detail).

The statement also says "Committee anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent" — basically, this increase isn't going to be enough, so expect more, but they're not sure how many.

Also, note towards the bottom where it says "...the Committee will continue reducing its holdings of Treasury securities and agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities...". Think about it. Reducing holdings means selling that stuff off. To sell things readily, you need to drop the price. In class you learned that dropping bond prices raises their interest rate. There's a lot of jargon there, but they're telling you they're following the theory in Chapter 11.

***

Nobel Prizes are awarded for important or seminal research done in the past. How far in the past depends on the field, and also how quickly or slowly the insight was adopted by others. It's also a bit like voting for members of a Hall of Fame in any field: sometimes they get people "in the Hall" right away, and sometimes it's delayed. Also, the prizes are only awarded to the living, so there's quite a list of economists who could have won the prize, but didn't. And often, it's awarded to more than one person, or idea.

This year it was won by 3 Americans who do research in monetary theory and policy. Ben Bernanke won (in part) for his research on intermediation (covered on Tuesday). Doug Diamond and Philip Dybvig won, mostly for a single paper written in the 80's, explaining how deposit insurance helps prevent bank runs. We did a MobLab on Tuesday with bank runs, and we'll do one on Thursday where bank runs are prevented by deposit insurance.

N.B. The Ben Bernanke discussed here for his academic work is the same guy who was chair of the Federal Reserve during the last financial crisis.

Us economists always have a mental list(s) of likely winners, so there aren't too many surprises. Bernanke could have won for more than one idea, and has been on everyone's short list for a long time. Doug Diamond was definitely on people's medium list. Dybvig was more of a stretch (to me), but macroeconomists do know that the big paper by either one of them is one they did together.

All of them are professors in their late 60's. Bernanke is an economist who worked at Princeton most of his career, and taught many principles classes like the one you're taking. Diamond is at the University of Chicago, and is actually a professor of finance in their business school. Dybvig is at a very good, but small school, called Washington University in St. Louis. He is also a finance professor in their business school. (At SUU, finance is now grouped with accounting, which is kind of unusual; the more typical way is to group it with economics, which is what we did until 2020). For graduate school, they went to MIT, Yale, and Yale.

A way that academics "keep score" is with citations (by other academics) for their papers. Google Scholar tracks this. More papers with more cites is better, although in some fields they cite more or less people so the numbers can be bigger or smaller.. Scholars can have their own pages on the site (in the Leavitt School of Business we're required to). Ben Bernanke is such a big deal he doesn't have one. But just putting in his name pulls up a list of papers with thousands of cites for each one. (Sometimes people build whole careers on one paper with hundreds of cites, so Bernanke is huge). Diamond does have his own page, showing 60K cites, while Dybvig's shows 20K. Their big paper is at the top of both pages with 13K cites all by itself.

Bernanke could have won for a bunch of things, but the award went specifically for the research he did on why the Great Depression lasted so long. He argued that banks and bankers, because of the intermediation they do, become repositories of qualitative information about borrowers and lenders. That information can't be easily replaced or replicated: if a bank goes bankrupt, that information is lost, and all of us suffer as a result. In short, it's not the financial crisis that makes banks fail, but rather it's the failure of banks that makes financial crises worse than they have to be.

Diamond and Dybvig looked more at what niche banks fill for society. Their insight was that the connect lots of small depositors with a smaller group of bigger borrowers. The problem with this is that the small depositors often want their money in a hurry, while the borrowers mostly prefer not to pay off their loans quickly. In short, the useful service banks perform makes them susceptible to a problem unique amongst industries: bank runs. In turn, runs cause bankruptcies, which reduce intermediation, making it harder for all of us to buy what we need when we need it if we don't have the funds. In their view, preventing runs from starting is really important.

It's worth noting that people involved in financial markets have mixed feelings about these three. Positive viewpoints can be found here and here. Others though, think their work (Bernanke's especially) made the most recent financial crisis worse than it needed to be (see here and here).

Nobel Prize winners often did work that shows up in principles texts. This year's prize is exceptional: big chunks of Chapters 10-12 were unknown 40 years ago before these three came along.

For November 1

Back in September, I posted about the interest rate decision of the FOMC (the part of the Federal Reserve that makes interest rate decisions).

At that time, I wrote that they'd have another meeting when we were covering Section III. It's today and tomorrow morning. I misspoke in class: they will make an official announcement of what they decided around 1 pm EDT, so 11 am here.

The expectation is that the FOMC will vote for another 0.75% increase in its interest rate target.

For October 27

It's the last Thursday of the month, so the real GDP estimates came out this morning.

Because it's the first month of the quarter, we get the first draft (called the "advance estimate") of the numbers from the last quarter (2022 III).

Every news item about this that you can find (like this one from CNBC) is based on this press release from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

The growth rate for real GDP came in at 2.6%/yr (annualized). That's better than what was expected, although forecasts like the ones I talked about a few weeks back have been improving.

Remember, real GDP is like stuff. Nominal GDP is like the pieces of paper called dollars we use to buy that stuff. It went up by 6.7%/yr (annualized) in the third quarter.

The difference is inflation. There's more than one measure of this, and the BEA produces ones called PCE. The PCE for GDP rose 4.2% (annualized).

† Note that it's only approximately true that you can add the inflation rate to the real GDP growth rate and get the nominal GDP growth rate. It works better for smaller numbers. If you check the numbers above, they don't quite add up. That's the way it's supposed to be, because it's only approximately correct to add them. Going for accuracy is a little more involved.

For October 25

This graph may give you some sense about why we're worried about inflation this year.

Once again, this is a nice graphic produced for free by Calculated Risk.

You don't have to know what the different colors mean (they're just different ways of measuring inflation). The point is they're all pretty much doing the same thing.

And inflation is higher than it's been in 30 years. Think about that: how old were your parents when inflation was high in 1990?

The blue shaded areas are recessions. Keep in mind that we're probably in a recession right now, but it has not been officially declared yet. The usual way that works is that about a year after the economy peaks, they officially pin down the start of the recession. So if the first two quarters of this year were weak, it would not be unusual for them not to have declared a peak yet.

Even so, you can see that inflation is not usually associated with recessions. That would make this one unusual.

Also note that inflation starts cranking right about the start of the Biden administration. I don't think that's grounds for blaming Biden (or Democrats in Congress) for the whole thing. Rather, inflation takes time to get going, so it's more plausible to blame it on all of the COVID-19 stimulus packages jointly: two under Trump and a mostly Republican-controlled Congress, another under Biden with a Democratically-controlled Congress, to which you could add the Democrats infrastructure bill from last year.

And, while for college students its hard not to think it's a good thing for number one, we should add the Biden student loan forgiveness program to that list of stimuli.

These are all important because inflation fundamentally is about too spending power being out of line with production. And what all of these programs do is push spending (shifting AD to the right). The theory in Chapter 8 tells us that ends up with higher prices. But, as I've remarked in class, pushing AD to the right with spending initiatives is what governments like to do, and they're just looking for an excuse. COVID-19 gave them one. Inflation is the result.

Comments

Post a Comment